So, assuming you have your Hartland "Sparky" as shown below or South Shore Line engine, lets start to work.

The first process is to take the engine apart. You should have a simple Philips screwdriver, another slotted screwdriver and a receptacle for the parts storage. Remove the trolley pole or pantograph. The car that I was using was equipped with a trolley pole and required the Philips to remove the screw attaching it to the car. Set the pole and screw into the storage receptacle.

Turn the engine over; there is a clamp affair that holds the motor truck onto the body. Take the slotted screwdriver and pry one end, a twist motion (between the engine block and clamp) to ease the clamp out beyond the end of the tab. Once it is free, do the same at the other end. The motor block should come out and the “light pole” with it. Twisting the clamp might take you a moment to get it worked over the tabs. Set the motor block aside.

There are two Phillips screws under the floor area, remove these and the cab should come of the base or frame. Set the cab aside. Remove the hoods from each end (lift up by the cab end and they should come off easily). Turn the frame over; remove the handrails and the 1/2 round air tank (I think that is what these are!), on each end by squeezing the tabs. Set these parts aside. The frame should be clear of all items.

The cab, remove the windows, headlight lenses, roof. Set the headlight lens and the windows aside.

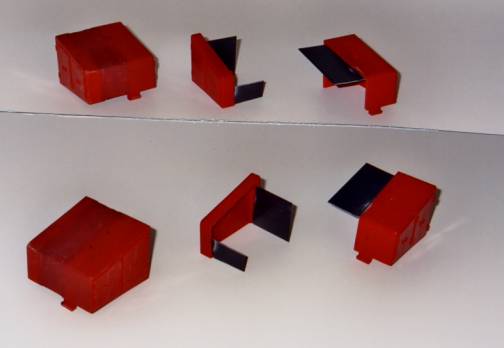

At this point, as shown above, the car shell, frame roof should be stripped of all the parts. Now, wasn’t that fun! You still have all your fingers, etc...!

Now the challenge is about to begin!

1. Some materials you need to have to complete this project are; Styrene sheets (Evergreen sheet styrene, .010 thickness), various wood strips, plastic angle pieces, etc.

2. I had already decided to add to the ceiling/roof height by 1 scale foot, and to add some rivet detail to this model. Some considerations you might want to think about, headlights, do you keep the ones on the model, or add new ones, window glazing, etc... I chose to add rivets, add new headlights, and add my own window details. To do this, I would use the styrene sheets to create a new side skin or sheets to the entire cab.

3. Beginning with the Cab, very carefully, I cut off the headlight barrels from the cab ends and sanded them somewhat smooth. I cut off the small piece under the side cab windows to make this smooth. You want the sides of the cab to be fairly smooth so when you glue on the styrene sheets, they attach with out too many big bumps that will show later on. If you model is a “show room” piece, that just arrived from the factory, you’ll want this area very smooth. If it is a working model, the engine during it’s life on your “railway” probably had some beating over the years and this, not being quite so prefect, will add some “texture” to it.

4. I also choose to make the front, lower window heights all the same. Taking some wood I filled in the lower portions of the front drivers window + the door window. You can see how this will eventually look in the next photo.

5. If you want to add to the floor to ceiling height, now is the time! Taking your styrene sheet, measure up a 1/2” (= 1 scale foot). Draw a new line that you will now use to line up the lower edge of the cab. Line up the lower part of the cab trace out each side and front panel. Use a good sharp pencil to out line the cab, window detail.

6. If you want to add rivet detail, this is also now the time. Draw some straight parallel lines about a scale 3 and 6 scale inches up from the lower edge of the styrene. A few equally spaced lines vertically, about 3 scale inches from the side edge, maybe one down the middle, and across under the window.

7. Now, using your ruler, mark off spacing, about every 6-scale inches were the rivet would be. Again be careful when doing this, as this is what people (including you) will later see.

8. There are many ways to create rivet details. I use a small center punch and a very small brass hammer, and lay underneath the styrene a small piece of soft plywood. Placing the center punch on the line and space marked off, and a very slight blow of the hammer, you are knocking in the rivet detail.

NOTE: You may want to practice a bit of scrap styrene materials to perfect your technique!

9. After knocking in all the rivet detail, check the “exterior” and see how it looks, did you miss any, some more needed in some areas, did I rivet across the lower doors areas where I should not have?

10. Very carefully, using a metal straightedge and knife cut the four walls apart. Leave some extra material at the top edge. This will be trimmed later after gluing. Carefully fit the sheets to each wall, do they line up OK, windows (Not yet cut out) look OK, rivet details is in the right places? Now cut some small wooden strips, which will act as the lower parts of the cab wall where there is now no material other that the styrene. When I measured the amount of wooden spacer or filler needed, I left a little edge of the styrene hanging lower then the new wooden filler piece and this will be used as a part of the flooring later on. See next photo.

11. Another thing I decided on was I wanted a door to “open” and so I very carefully cut out one door, and made this an open door way as shown in the previous photo. Set the door aside, use some styrene and wood to increase the door height, as we will add this on later.

12. So, if things look OK, smear on some glue onto one cab side, and lay on the styrene materials, clamp or add weights to insure a good strong bond between the cab and the styrene. Let this sit over night at least (or say 10-12 hours). I wanted the styrene to be well bonded to the body before I moved on. Glue all four sides, and add the lower wood fill part. Make sure this wooden piece is parallel with the car sides.

13. After the glue is dry, carefully start to cut out the window areas. I also started to prime and paint the styrene as I went along.

14. For the “hoods” I carefully cut length wise, and added some heavy plastic pieces to the insides, so that the hoods would be wider. After they were carefully glued together, I added some filler wooden pieces for strength and then carefully added some styrene (with rivet detail) over the top and front side. Again leaving some extra materials to be trimmed off later

The next photo shows the hoods being clamped together to make the wider hood.

15. For the roof, I filled in with wood and modeling filler to make the roof skin smooth, and added some to the inside ceiling to make this smoother. I cut small pieces of wood for trolley cleats and also cut some trolley boards to length. I made these so they will extend over the cab roof ends about 3/4” (18”scale inches). I started to paint the roof a reddish color, along with the boards.

16. For the frame, I cut off the rounded extension between the two-journal boxes at the lower edge of the frame to make this part straight (on each side).

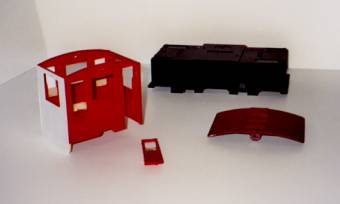

17. The next photo shows the cab, cab door, main frame, roof. You can see the cleats I have sanded to fit the roof contour and glued in place.

In Part 2, we will finish the cab, roof, and frame. We will add the trolley pole and base, trolley pole hooks, Kadee couplers, interior details, and paint and finish the model.

Karl Johnson was raised in central upper Massachusetts where the local Bus Company still used

“Street Railway” in it’s name. So, yes, he rode the street railway line each day to and from school, but they had

advanced (?) to using new modern GM busses. There were

remains here and there of the old railway line; i.e., a crossing with the

Boston & Maine on River Street, or an old piece of rail showing through the blacktop out on Summer street. He was once watching the street repair guys pulling out some old step

type rail from an intersection, when they offered to bring it to his house. Since our house and yard was at the top of a twenty plus flight of stairs, I

could not see where I would have put that track! There was also an old New Haven branch that went trough

the local towns. After moving from one city to the next, he was able to ride the local switcher during his

summer days off from school. It also allowed time to play with model trains at

home and on summer vacations to go to the Seashore Trolley Museum, where his

father volunteered as a motorman, and, of course, he helped to change the poles at

the ends of the line. For a while, he was even a ride operator at a local amusement park. Eventually, he found himself volunteering in the museums shop area, working on track, and

learning about and helping to move these crippled old cars with no motors, just

set onto trucks around the museum. During the summers, he got himself

employed by the museum, first as a ticket agent and car barn “host”, and then later

in the shop restoring streetcars, running maintenance on the small fleet

of cars operated for the public, and learning how to operate the various

machines the museum had. After graduation from High School, he spent much of his employment time not only at the museum,

but also a local eatery, a construction company, etc. One fall, Karl decided to take off and head west to get out of the snows

of Maine. He left in mid January, delayed a day due to yet another snowstorm. He found himself as a

volunteer at a local streetcar museum, and later in the year found employment at

a real transit company that still maintained a good size fleet of PCC cars,

and a small assortment of work and excursion cars. As his employment continued working for the transit company, working various shifts, he began

working on the latest modern equipment, only to be dragged away to work on a small

Summer “historic” car operation, that would operate down one of the busiest

main streets in America. Many years later, Karl worked on a cable rope system and assisted in the rebuild specification

for the overhaul of a small flock of PCC cars. He even traveled to Italy to look

at yet another group of 1928 built cars and as this lesson is written still

enjoying his employment with the Transit Company. In 2000, he started to collaborate with a gentleman in the United Kingdom who was producing

1:24th scale traction parts, and attempted to help him sell these

items here in the US. As a result of that experience, I could see that there

is a small market for G scale traction items, which could be sold here in the

US. More manufacturers are bringing out traction items (Hartland, LGB

will have a New Orleans car along with it’s

European trams). Light Rail Products was created to fill in the vacuum, creating detail parts for traction buffs

everywhere. Please see our web site at www.lightrailproducts.com.